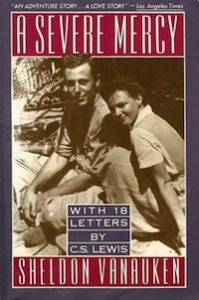

A Severe Mercy

by Sheldon Vanauken

A Severe Mercy chronicles the courtship and marriage of Sheldon and Jean Vanauken, followed by Jean’s untimely death at the age of 40. At its core, the memoir is a story of conversion and salvation within a marriage, and of a couple who comes to believe that God’s love is the true source of all human love. Known to their friends as Van and Davy, the couple lived during the time of the world wars. Davy died in 1955, and Van outlived her by nearly 40 years. Although Van wrote the memoir about 20 years after Davy’s death, the depth of the bond between them means that when he uses the word “we” in the narrative, it reads like an “I”.

A Severe Mercy chronicles the courtship and marriage of Sheldon and Jean Vanauken, followed by Jean’s untimely death at the age of 40. At its core, the memoir is a story of conversion and salvation within a marriage, and of a couple who comes to believe that God’s love is the true source of all human love. Known to their friends as Van and Davy, the couple lived during the time of the world wars. Davy died in 1955, and Van outlived her by nearly 40 years. Although Van wrote the memoir about 20 years after Davy’s death, the depth of the bond between them means that when he uses the word “we” in the narrative, it reads like an “I”.

Prior to their Christian conversion, Van and Davy had a strong “pagan” love that rooted itself in “the mystery of beauty” (31). They erected what they called the “Shining Barrier” to prevent the “creeping separateness” of self-regard from destroying their love (37). Part of the “Shining Barrier” were principles that guided their actions, including the Principle of Spontaneity, the Principle of the Affirmative, and the Principle of Courtesy (38-39). Their structured plan for remaining in love throughout their lifetime required hard work – adherence to the principles, complete sharing, and total trust. They held “Navigators’ Councils” frequently to discuss the state of their relationship, and when in doubt about a decision always acted according to the “Appeal to Love” – they must do what would be the best for remaining in love (41).

Their love was initially “pagan” because they were both agnostic, considering Christianity a nonsensical belief system. Entranced by eros and beauty, they made several pagan decisions in their relationship: They agreed that if one should die, the other must commit suicide so that they could share the experience of death immediately. They also agreed that they would not have children, because they could not share pregnancy, childbirth, and parenting perfectly between them. In these ways, they allowed a pagan lifelessness to enter their marriage.

During their studies at Oxford, they come into contact with many Christians who, to their surprise, were interesting, kind, and intelligent. Intrigued, they decided to give Christianity “another look” (82). This second look, fueled by the publications and personal letters of Oxford professor C.S. Lewis, sparked the couple’s conversion to Christianity. Davy converted first, and Van, after an intense period of doubt, followed her. C.S. Lewis pivotally aided Van’s conversion by fearlessly and frankly engaging him on the points with which he struggled most, such as the difficulty of making an initial leap of faith. Through Lewis and other friends, Van “discover[ed] a Christ who was a blazing reality” and chose to believe in Him (131). From their conversion onward, the light of Christ invaded the Shining Barrier and radically transformed the Appeal to Love. God’s love became more important than their love for each other. Van and Davy moved from “Us” to “Us and God” (210). However, the final stage, moving to “God and Us,” did not happen until after Davy died.

At the age of 40, Davy became seriously ill. Her dying time was a period of renewed love between the couple, as Van completely devoted his life to caring for her, even successfully talking her out of a coma at one point. Her imminent death was an occasion for Van to uphold his Christianity by truly bearing his wife’s burdens. Ultimately, Davy’s death contributed to Van’s ongoing conversion. His retrospective examination of their life together revealed his latent jealousy and potential hatred of God, feelings he had not known existed in him. Remembering Davy’s life as a whole gave him a glimpse of eternity and inspired a longing for Heaven. He came to understand that “we have not always been or will not always be purely temporal creatures…[W]e were created for eternity” (203). In this sense, Davy’s death was, as C.S. Lewis called it, “a severe mercy” (210). Her death brought about his reconciliation to God, perhaps the salvation of his soul, but at the severe price of loss.

The author’s writing is characterized by an old-fashioned beauty. Van intersperses the text with his own poetry, along with the poems of several other friends, and they are a joy to read and contemplate. His poetic voice remains in the prose as well, especially when he speaks about Davy. The letters written between Van and C.S. Lewis are also engaging, as you can see their affection increase over time. It’s clear that the divine hand was at work in these two friends’ lives: Lewis would suffer his own “grief observed” when his wife died young, and Van was well-equipped to help him through it.

With refreshing honesty, Van reveals the details of his marriage. He makes plain the secret structure of their relationship – the various nicknames they gave to important days in their lives, their inside jokes, the poems written only for each other’s eyes. The sharing of these intimate details reveals that the marriage truly contained goodness unburdened by hiddenness or shame. These details also make the reader feel present during the events of their lives and invite the reader to see love as Van does, as “the final reality” of all things (164).

A Severe Mercy witnesses to the salvific role of marriage. Van and Davy worked to ensure salvation for each other, Davy even offering up her life privately to God in exchange for Van’s salvation. Van later did the same, offering his life “for her good, whatever it might be” (159). The Appeal to Love turned into an appeal to salvation, an appeal to God, both realizing that divine love is higher than merely human love. A Severe Mercy shows the triumph of Christian selflessness through a marriage well-lived, a marriage submitted to the will of God. It is a witness to the possibility of truly becoming “one flesh,” in spite, or maybe because of, mistakes, doubts, and suffering.

About the reviewer

Juliana Vossenberg is the Summer 2015 intern for the Secretariat of Laity, Marriage, Family Life, and Youth at the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Disclaimer: Book reviews do not imply and are not to be used as official endorsement by the USCCB of the work or those associated with the work. Book reviews are solely intended as a resource regarding publications that might be of interest to For Your Marriage visitors.